I get a lot of questions about why individuality is one of the three core tenets of The Cancer Remission Mission. While it may seem obvious that individualized cancer care should be a focus of all cancer care, the reality is that it’s not.

Commonly, there is a drive in medicine to create “standards of care”. Interestingly, the standard of care is a legal term, not a medical term. Basically, it refers to the degree of care a prudent and reasonable person would exercise under the circumstances.

It’s the benchmark that determines whether professional obligations to patients have been met. Failure to meet the standard of care is negligence, which can carry significant consequences for clinicians.

But, the standard of care is not optimal care. Rather, it is a continuum, with barely acceptable care at one end, and the ultimate in care at the other end. In terms of malpractice liability, clinicians just need to make it onto the continuum, even if near the barely acceptable care end. Of course, in terms of patient safety and clinical outcomes, clinicians should aim in the direction of optimal care.1

Now, while this can seem as though it’s all about reducing liability to the clinician should they be litigated, there is a more altruistic side to the concept.

Standards of care are often very research-driven, trying to provide the best care, sitting on the “ultimate care end of the continuum”. It’s an attempt to make sure that each patient is actually treated with the most validated, beneficial treatments of the time.

The challenge with this, however, is that it can almost lead to tunnel vision where a clinician only focuses on the numbers and the outcomes seen in studies, rather than looking at the broader context for that individual.

Recently, I had an interaction with a new patient whose story exemplified the exact reason why individuality is so important in cancer care and cancer recovery.

Let’s call this patient Carrie.

Carrie had a very low-grade (stage 1), low-risk form of breast cancer that was caught early. They not only excised the lesion with clean margins, but they also took several lymph nodes which were all totally cancer-free.

Despite this successful outcome, 14 rounds of chemotherapy and 3 rounds of radiation were recommended. Frankly, a pretty aggressive treatment plan for such an early stage, low-risk cancer.

Carrie followed this recommended treatment diligently because she figured that was the best recommendation and she wanted to reduce every risk possible.

Following this treatment, it was recommended that she use a specific medication for 10 years to reduce her risk of recurrence.

By the time Carrie came to see me, she had rotated through four medications trying to find one that didn’t leave her completely debilitated. These medications had left her exhausted with crippling joint pain that was making it hard to walk around her home, let alone go on the lengthy hikes she used to do, and love, before her treatment.

When Carrie decided to dig into understanding things for herself, because nobody would give her the actual data, she learned that this medication only reduced her risk of recurrence by two percent (2%) over a 10 year period. Two percent? Two percent!

But here is the kicker…Carrie who loved to be active, could barely move, and yet many studies have shown that physically active women have a lower risk of breast cancer than inactive women.

In a 2016 meta-analysis that included 38 cohort studies, the most physically active women had a 12–21% lower risk of breast cancer than those who were least physically active.2

So, the question becomes – what is the bigger risk factor?

Beyond that, it’s a well established fact that cancer survivors have greater rates of depression and anxiety compared to non-cancer survivors – nearly 30%, which is three times the national average. This is actually an independent risk factor for recurrence and also increases the risk for suicidality.

Again, what’s the bigger risk factor?

Is it more important that Carrie be able to live a happy and active life, or take a medication that leaves her house-bound, lacking activity and social interaction because it reduces her risk by two percent?

Carrie’s clinicians were certainly striving to meet the standard of care and, in fact, exceed it. However, where that well-intentioned goal got lost is when Carrie stopped being heard and listened to regarding the negative impacts on her life.

Ultimately, our discussion culminated in Carrie being confident that she could safely discontinue this medication. She also could do this because I was able to offer additional support to reduce her risk factors that were in alignment with her desires for a robust quality of life, rather than just quantity of life.

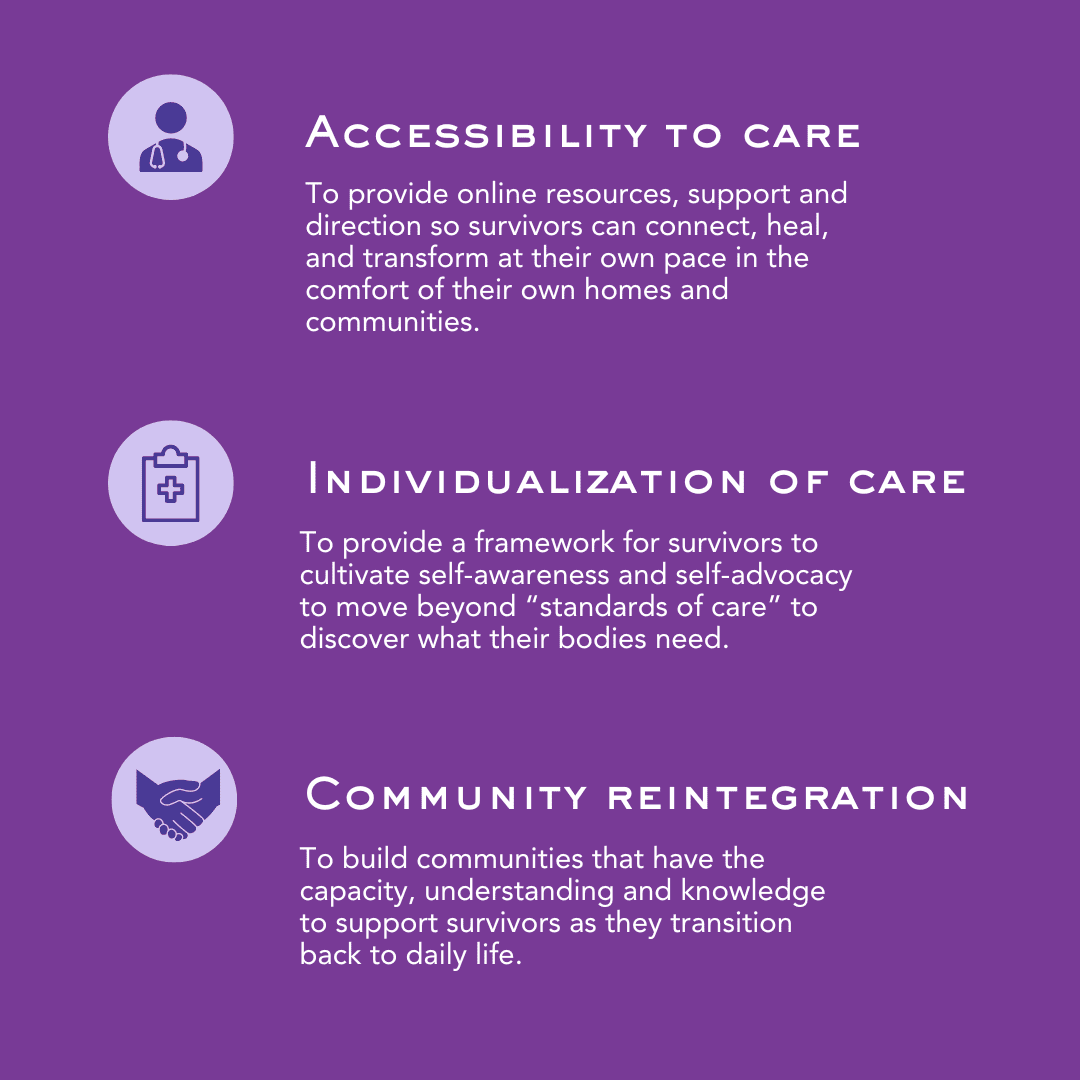

This is why I created the tenet of Individualization of Care in The Cancer Remission Mission and why it is the basis of my book, The Opportunity in Cancer.

The tenet and goal is: “To provide a framework for survivors to cultivate self-awareness and self-advocacy to move beyond “standards of care” to discover what their bodies need.”

This is how we create Thrivers!

1. Vanderpool D. The Standard of Care. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2021 Jul-Sep;18(7-9):50-51. PMID: 34980995; PMCID: PMC8667701.

2. Pizot C, Boniol M, Mullie P, Koechlin A, Boniol M, Boyle P, Autier P. Physical activity, hormone replacement therapy and breast cancer risk: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Cancer. 2016 Jan;52:138-54. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.10.063. Epub 2015 Dec 11. PMID: 26687833.